Synopsis: This article explains the concept of sustainable investing, why it’s gaining traction across a broad section of retail and institutional investors and the four prominent investment approaches or strategies that are considered under this investment practice.

Introduction

Sustainable investing is the idea that investors can achieve a positive societal impact with their investments. Optimally, this should be accomplished without sacrificing long-term financial returns. The possibility of achieving these dual objectives is what investors in increasing numbers find attractive. In recent years, a growing number of individual and institutional investors have been adopting sustainable investing strategies. Moreover, the same investor groups anticipate that sustainable investing will become even more important over the next few years. But investors should be aware that the successful implementation of such strategies call for the application of basic

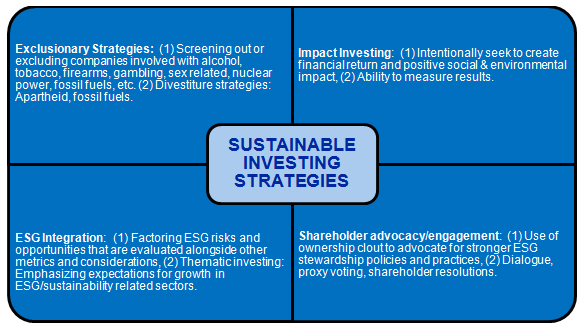

There are a variety of sustainable strategies and while the financial return profiles associated with each of these will vary, most practitioners agree that these encompass four notable approaches: (1) Exclusionary strategies or the screening out of companies from investment portfolios for a variety of reasons, including ethical, religious, as well as other strongly held beliefs, such as environmental concerns or involvement on the part of companies in specific business activities, (2) Impact investing or investing to achieve a targeted social or environmental objective that is measurable, (3) Integrating environmental, social and governance (ESG)considerationsas a proactive and integral component of the investment research and portfolio construction processes, including companies with social and environmental objectives that some investors believe can serve to minimize certain vulnerabilities, such as the risk of lawsuits from employees or toxic spills, and look for these goals as predictors of financial performance, and (4) Shareholder and bondholder advocacy and engagement in an effort to influence corporate behavior. These are not mutually exclusive strategies and investors can, and are often found, to engage in one or more of these at the same time. Moreover, it’s not always entirely clear where one strategy begins and another ends, as these can also morph into one another. While the above definitions attempt to broadly define sustainable strategies, there are potentially other investing approaches that aim to achieve a positive societal impact and financial returns that might not lend themselves to easy classification. Falling into this category, for example, is investing in or financing microfinance institutions that seek to provide banking services to poor families and micro-entrepreneurs.

Sustainable investing in not new. Its origins the US can be traced to religious considerations practiced by the Methodist movement in the 18th century. Historically, the Methodist church opposed investments in companies involved with liquor or tobacco products or promoting gambling, which was expressed in the form of positive and negative screening. As for investment products, the first public offering of a screened investment fund is reported to have occurred in 1928 when an ecclesiastical group in Boston established the Pioneer Fund. The simple screening approach has been expanded to include divestiture, social impact analysis well as shareholder activism, practices that were encapsulated under the label of sustainable and responsible investing or SRI. More recently, this term has begun to fade somewhat from contemporary usage—being supplanted by the idea that the performance of companies on sustainability issues such as social, environmental and governance factors, is linked to the financial performance of these same companies. This had also translated into the belief that investing in sustainable companies permits investors to attain long-term competitive financial returns while at the same time achieving a positive societal impact.

Sustainable investing has been gaining footing among individual, high net worth as well as a wide range of mainstream institutional investors. These range from public pension funds, endowments, and foundations, to mention just a few, as well as traditional investment management firms. Historically, much of the focus of sustainable investing has been on equity-oriented strategies. As more investors seek to apply a sustainable approach to their entire portfolio of securities, attention has begun to shift to other asset classes, including fixed income and real estate. This approach in one form or another has also found its way into alternative investments, such as hedge funds and private equity portfolios.

According to the 2016 Global Sustainable Investment Review, an estimated $23 trillion in worldwide assets under management are linked to SRI investments[1]. This represents a strong increase of 25% over the last two years when about 18 trillion was sourced to sustainable strategies.According to the same report, assets sourced to sustainable strategies reached $8.7 trillion, or an increase of 33% since 2014. While these numbers are likely inflated due largely to some confusion over terminology and to double counting, it’s difficult to argue that the trend in favor of SRI investing or sustainable investing is experiencing a strong upswing.

Sustainable Investment Strategies

The four prominent sustainable investment strategies are illustrated and summarized below:

Sustainable Investment Strategies at a Glance

Exclusionary/Divestment Strategies

Exclusionary strategies involve what some refer to as negative screening or the exclusions of companies or certain sectors from portfolios based on specific ethical, religious, social or environmental guidelines or preferences. Traditional examples of exclusionary strategies include avoiding any investments in companies that are fully or partially engaged in gambling and sex related activities, the production or manufacturing of alcohol, tobacco or firearms, or, in some cases, even atomic energy. These exclusionary categories have been extended in recent yearsto include additional considerations, for example, firms that are the subject of serious labor-related actions or penalties by regulatory agencies or demonstrate a pattern of employing forced, compulsory or child labor, or firms that exhibit a pattern and practice of human rights violations or are directly complicit in human rights violations committed by governments or security forces, including those that are under US or international sanction for grave human rights abuses, such as genocide and forced labor.

In general, this investment approach, when viewed through the prism of mutual funds, and in particular equity oriented mutual funds, has produced an uneven financial track record and in some cases delivered a poor financial outcome.

Divestment strategies, on the other hand, include the liquidation or avoidance of individual firms due to their link to particular business activities or a geographic location. For example, in the

1970’s and 1980’s this included divestment of firms located or doing business in South Africa in an effort to end apartheid practices or, more recently, fossil fuel companies, involved in coal, oil and gas, in an effort to bring about a reduction in carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions and mitigate climate change.

ESG Integration

ESG integration involves an analysis of ESG issues deemed material to company performance that are, in turn, systematically considered through quantitative models or qualitative analysis in buy/sell decisions or position weightings in order to enhance risk-adjusted returns or reduce portfolio volatility. This approach may include screening based on ESG criteria that determines a security’s eligibility for the portfolio.

ESG integration is gaining traction among investors, in part, on the strength of studies on financial performance of sustainable investments that seem to demonstrate improved financial portfolio and stock performance when ESG factors are analytically applied. However, the results are still inconclusive.

A variation on the ESG integration strategy is thematic investing, an approach based on expectations of growth in ESG/sustainability-related sectors. For example, this may include investment s in agriculture, clean energy, such as solar energy, wind, and clean water, to mention just a few. The recently popular version of thematic investing in the fixed income sphere consists of investments in green bonds, which may also be viewed as impact investments, where the proceeds are used to achieve environmentally sustainable purposes.

Impact Investments

Impact investments are investments made into companies, organizations, and funds with the intention to generate measurable social and environmental impact alongside a financial return. Impact investments can be implemented in both emerging and developed markets and can be made across asset classes, including but not limited to cash equivalents, fixed income, venture capital, and private equity. In each instance, the objective is to direct capital to address the world’s most pressing challenges in sectors such as sustainable agriculture, renewable energy, conservation, microfinance, and affordable and accessible basic services including housing, healthcare, and education.

Historically, impact investments have targeted a range of returns from below market to market rates, depending on the investors’ strategic goals. While this may still be the case for certain investors, for example, not-for-profits, retail and institutional investors are increasingly seeking to achieve market-based returns as a prerequisite to investing in this segment.

Issues of scale, diversification, liquidity, and costs present challenges when it comes to making individual direct impact investments and therefore, with some exceptions, investing in managed funds is a more viable strategy for retail as well as many institutional investors. One exception is a direct investment in green bonds–fixed-income securities, both taxable and tax-exempt, that raise funds specifically to finance new and existing projects with environmentally sustainable benefits. Also considered to qualify as ESG investments, these may include securities issued by sovereigns, development or supranational banks, corporations, states, cities and local government entities, such as water, sewer or transportation authorities.

Shareholder and Bondholder Advocacy and Engagement

Shareholder and bondholder advocacy and issuer engagement are approaches that, for equity or stockholders, rely on influencing corporate behavior through direct corporate engagement, filing shareholder proposals and proxy voting. There are numerous examples of this, but three in particular include influencing executive compensation, the composition of the board of directors and climate risk disclosures as well as climate-related action plans. On the other hand, for bond owners, unlike stock owners, this approach relies on securing additional information, communicating by means of adirect dialogue ESG related issues to management in an effort to influence issuer behavior, including companies, sovereigns and municipal entities, or modifying bond indenture terms and conditions.

It should be noted that shareholder initiatives do not produce direct or near-term financial results but can lead to improved long-term performance aligned with changes to a company’s behavior and improved competitive positioning.

Implementing Sustainable Strategies

Investors can implement sustainable investing strategies by purchasing individual stocks, bonds, mutual funds, Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs), Unit Investment Trusts (UITs) and even closed-end funds. But regardless of the approach, the same basic investment principles apply before a purchase decision is made. That is, investors have to conduct fundamental due diligence and analysis to evaluate the investment to make sure that it fits with their return requirements, risk tolerance, income needs and asset allocation goals. In addition, the investment’s sustainability profile should be aligned with the investor’s goals and objectives. Typically, due diligence efforts should focus on management characteristics and stability of organization, historical performance or financial track record, expenses as well as any other investment specific relevant considerations which will likely vary from one investment to the next.