Sustainable Bottom Line: Cash holdings in mutual funds and ETFs, conventional and sustainable, have implications for performance, liquidity management, and how investors experience market exposure.

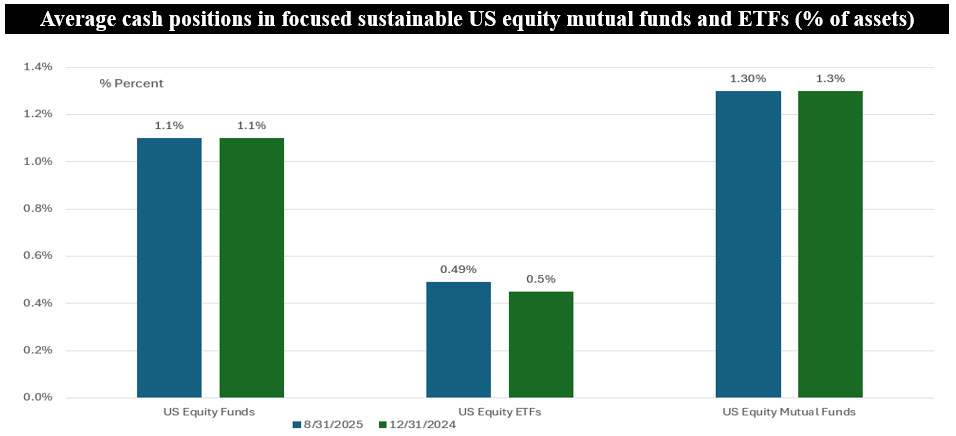

Notes of Explanation: Cash positions reflect the average of cash held in US equity funds, including Large Blend funds, Large Growth funds, Large Value funds, Mid-Cap Blend funds, Mid-Cap Growth funds, Mid-Cap Value funds, Small Blend funds, Small Growth funds and Small Value funds, a total of 325 mutual funds/share classes and ETFs with $218.6 billion in assets under management as of August 31, 2025. Sources: Morningstar and Sustainable Research and Analysis LLC.

Observations:

• One of the less visible but important distinctions between equity mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs) lies in their cash holdings (cash and cash equivalents). While both vehicles invest primarily in stocks, ETFs tend to maintain lower cash balances than traditional mutual funds. This structural difference, which applies to conventional funds as well as focused sustainable funds, has implications for performance, liquidity management, and how investors experience market exposure.

• Industry studies, including work by Morningstar and the Investment Company Institute, have long documented that open-end mutual funds generally carry more cash on their balance sheets than ETFs. Cash levels in equity mutual funds often range from 1% to 5% of assets, though this can rise during periods of heightened redemptions or market uncertainty. By contrast, most ETFs operate with minimal cash—often less than 1%—aside from dividend accruals, margin collateral for derivatives, or operational needs. In line with these studies, at the end of August 2025, cash positions in focused sustainable U.S. equity mutual funds were 2.2X higher than they were in ETFs, largely unchanged from cash positions at the end of 2024.

• The reason for this is that mutual funds must be ready to meet daily investor redemptions in cash. To avoid forced sales, managers hold cash cushions. ETFs, however, rely on their unique in-kind creation and redemption mechanism, where authorized participants exchange baskets of securities rather than demand cash. This structural feature significantly reduces the need for cash buffers inside the fund portfolio itself. Furthermore, ETFs can minimize taxable gains distributions by transferring securities in-kind, reducing the incentive to raise cash through sales. Finally, active mutual fund managers may boost cash tactically when they lack conviction in available investments, a choice less common in index ETFs.

• The difference in cash positions has various effects—both good and bad—on investors. On the positive side of higher cash levels in mutual funds is that they provide a cushion during market downturns. When markets decline sharply, funds with more cash on hand may fall slightly less than their benchmarks. This was evident during episodes of market stress, such as the 2008 financial crisis and the pandemic-driven volatility of early 2020. However, in rising markets, cash creates a performance drag. A portfolio that is 97% invested in equities will, all else equal, underperform a fully invested benchmark. This “cash drag” has become more noticeable in the ETF era, where investors can see sharper tracking between an index ETF and its reference benchmark. It should be noted, however, that for diversified portfolios focused on maintaining specific asset allocations, these mixed impacts may be undesirable.

• Another implication relates to tracking error. ETFs’ low cash balances mean they tend to stick closely to their target index, while mutual funds’ variable cash positions can generate deviations. For investors seeking purity of exposure, this makes ETFs more predictable.

• That said, the interest-rate environment matters. In the past, near-zero yields made cash a costly allocation. Today, with cash yielding 4–5%, the opportunity cost of mutual funds’ cash cushions is less severe. Still, the principle remains: higher cash generally means lower volatility relative to the overall stock market.

• For investors, the key takeaway is that cash is not a neutral position. In mutual funds, it reflects both structural needs and managerial choices. In ETFs, low cash levels are a structural feature that enables tighter index tracking but also removes the modest cushion cash can provide in turbulent markets. Understanding these differences helps investors align product selection with their risk tolerance, return expectations, and portfolio strategy.