Recent article continues to sow and perpetuate confusion between varying strategies and approaches that make up the sustainable investing landscape

An article in the Financial Times dated October 15, 2019 entitled “ESG Hardliners Blacklist $16 trillion U.S. Treasuries Market” by Alice Gledhill is the latest in a string of many that continues to sow and perpetuate confusion between varying strategies and approaches that make up the sustainable investing landscape, in particular by conflating ESG funds or ESG investors, taken to mean funds or managers that integrate ESG in their investment management process, and values-based investing and negative screening or exclusionary approaches. This muddying up of two unlike sustainable investing approaches has also crept into the day-to-day conversation and unless checked, is likely to deter investors, in particular individual investors, lead to disappointment on the part of clients of all types, and expose asset managers to potential reputation risk, regulations and worse, financial liabilities.

According to the FT article, some of Europe’s strictest ESG funds “are snubbing the world’s most liquid investment — the $16 trillion U.S. Treasuries market.” The $33 billion-euro ($36 billion) French state pension plan and ESG funds run by the likes of Erste Asset Management, Joh. Berenberg Gossler & Co. and Union Investment all shun Treasuries based on the U.S. government’s stance on capital punishment or climate change. The exclusions rank the U.S. alongside arms makers, tobacco producers and distilleries in falling foul of environmental, social and governance standards. The article goes on to quote Rupini Deepa Rajagopalan, head of the ESG office at Berenberg Gossler that investments in U.S. Treasuries are to be avoided based on the existence of the death penalty, nuclear weapons and non-participation in global environmental agreements, such as the Kyoto Protocol. Boycotting Treasuries highlights a key challenge for ESG managers that often divides the industry — defining what is and isn’t a “responsible” investment. It also shows how ESG investors have to balance ethical standards against the need to make money, particularly when avoiding large liquid markets makes it harder to spread risk or to react quickly in a crisis.

Boycotting US Treasuries not the same as ESG investing

Unless boycotting Treasuries is linked to their potential loss of value in the future, client mandates or legal or regulatory restrictions, excluding these instruments should not pose a challenge for ESG managers. As used by the author of the article and others, the term ESG funds, ESG managers or ESG investing characterize a range of different sustainable investing approaches with varying strategy implications that include limits on the types and number of sectors and companies available to the funds. These can have varying social and environmental impacts or outcomes and they can also potentially lead to a negative impact on portfolio performance. This is in contrast to the accepted definition of ESG investing or ESG integration. As such, this reinforces a widening area of confusion and misunderstanding around sustainable investing practices and expectations.

Range of sustainable investing approaches

The sustainable investing landscape, even as it continues to evolve, encapsulates a range of approaches and products that most practitioners agree include the following[1]:

- Values-based investing, which also goes by the names ethical investing social investing or religious investing, refers to pursuing investment strategies that conform to religious, ethical or social norms, for example, aligning investments with Christian or protestant or Islamic values. This is usually achieved via screening out industries and companies.

- Negative screening or exclusions. Screening out or excluding companies from investment portfolios for a variety of reasons, including ethical, religious, as well as other strongly held beliefs, such as environmental concerns or involvement on the part of companies in specific business activities, such as gambling and sex related activities, the production or manufacturing of alcohol, tobacco or firearms, or atomic energy. Exclusions can also extent to entire sectors, such as fossil fuels.

- Impact investing or incremental investing to achieve a targeted social or environmental objective that is measurable, for example, investments in companies that develop or offer products or services seeking to protect the environment or provide environmental solutions intended to reduce greenhouse gas emissions or companies that promote workplace diversity, human rights and community relations, advance educational initiatives or attempt to alleviate housing shortages and poverty, to mention just a few.

- Related to this is thematic investing. A less rigorous approach relative to impact investing that targets specific areas of investment, such as solar energy, wind energy, environmental solutions. Green bonds or social bonds are also examples of thematic investing.

- Integration of environmental social and governance (ESG) factors in the investment management process and decision making where such factors are considered relevant and material to investment decision making. This approach is employed as a proactive and integral component of the investment research and portfolio construction processes that can serve to minimize certain vulnerabilities and risks and at the same time benefit from positive ESG attributes as predictors of long-term financial performance, and

- Shareholder and bondholder engagement and advocacy in an effort to influence corporate behavior; and also a more active deployment of proxy voting.

Exclusions versus ESG integration

Focusing specifically on the article mentioned above, the author refers to manager strategies that rely on an exclusionary approach predicated on the avoidance of investments in certain companies, industries and even sovereign issuers, as is the case with US Treasury obligations. In doing so, the managers may assume the risk of underperformance while at the same time aspiring to achieve social and/or environmental goals.

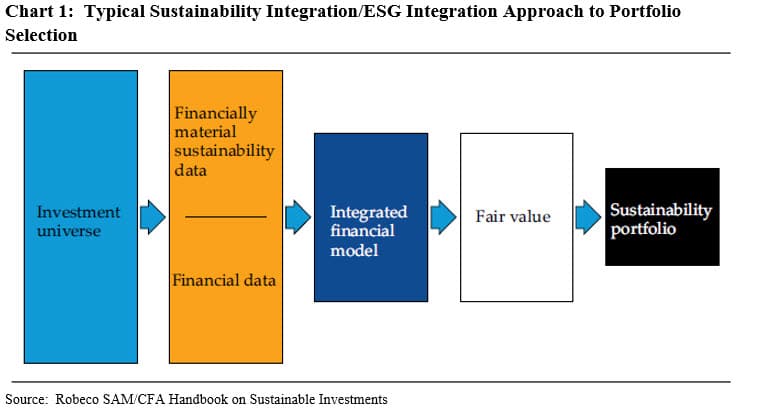

This contrasts with an ESG integration strategy that combines ESG data analysis with other investment considerations. ESG investing is defined as the consistent and systematic explicit inclusion by asset managers of ESG risks and opportunities into traditional financial analysis and investment decisions where such considerations are deemed relevant and material. Refer to Chart 1 for an illustration of this process.

As further explained by one investment management firm that has adopted an ESG integration approach, Franklin Templeton Investments (FII), in its published Responsible Investment: Policies and Principles, ESG factors can have a material impact on the value of companies and securities. Examples of ESG factors include natural resource use and scarcity, governance controls, product safety, employee health and safety practices, and shareholder rights issues. FTI notes that it believes these issues should be considered alongside traditional financial measures to provide a more comprehensive view of the value, risk and return potential of an investment.

Regardless of approach disclosures are key

It should also be noted that sustainable investing approaches are not mutually exclusive and some managers combine one of more approaches. Regardless of the approach or products offered, however, it is key for investment management firms to offer investors who are attracted to sustainable investing a clear explanation of their approach and strategies, how such strategies are implemented, their impact on investment decision making and outcomes, both from a financial return point of view and, to the extent possible, in terms of social, environmental and governance outcomes. The same applies to all financial reporters and others.

[1] Refer also to previous article on this topic entitled ESG Integration should not be Confused with Responsible Investing Practices.