The Bottom Line: According to the Economist magazine, dubious green funds are rampant in America but the article is misadvised regarding the sustainable funds market.

0:00

/

0:00

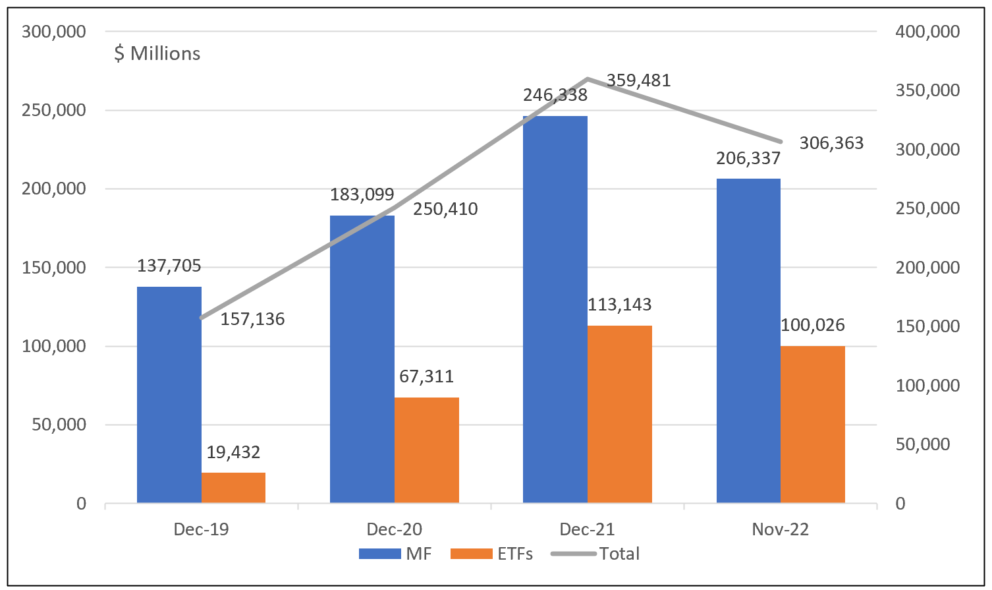

Growth in sustainable mutual funds and ETFs by assets: Dec 2019 – November 30, 2022 Notes of Explanation: Data source: Morningstar Direct. Research by Sustainable Research and Analysis.

Notes of Explanation: Data source: Morningstar Direct. Research by Sustainable Research and Analysis.

Observations:

- The December 3, 2022 edition of the Economist includes an article on green investing entitled “Uncle Sham” that’s accompanied by the tag line “Dubious green funds are rampant in America.” The article discusses the recent large-scale shifts that have taken place in the classification of European Union (EU) sustainable funds due to the implementation of the EU’s sustainability disclosure regime that went into effect in July. Many funds, according to the article, have shifted their classification from the highest grade to “light green.” This has exposed European fund managers to accusations of greenwashing, according to the article. The same article goes on to report that recent research published in the Review of Finance suggests that American firms are doing worse. “When it comes to sustainable investing, Wall Street stalwarts appear to run a fully fledged laundromat of exaggerated sales pitches and bogus claims.” The article is misadvised regarding the sustainable funds market in at least four ways (the reference to sustainable funds encapsulates a wide range of investing approaches from values, impact and thematic to ESG integration).

- First, the Economist article reaches its conclusion by keying off research just published in the Review of Finance in which the authors examined funds that have signed up to the UN-sponsored Principles for Responsible Investment (PRI), “a scheme that investment managers can sign up to certify that they take account of environmental, social and governance (ESG) principles when making investment decisions.” Examining a fourteen-year period from 2003 to 2017, researchers found no sign that the portfolios of PRI signatories in America had higher ESG scores, across a range of metrics, than non-signatories.

- Facts: The PRI was launched in 2006 to set forth an aspirational set of six best practices for responsible investment. Much of the growth in the number of signatories commenced around 2015, not coincidentally, the year 196 parties adopted the Paris Climate Agreement. As for funds in the US, the growth in the number and assets of sustainable funds, now at $306.4 billion according to Morningstar, didn’t really begin to take off until the start of 2019. Many US sustainable funds, either rebranded or operating pursuant to a socially responsible mandate, don’t have a track record that extends to 2017, let alone 2003.

- Second, the Economist posits that funds managed by PRI signatories should have higher ESG scores.

- Facts: PRI signatories commit to a set of six best practices, the first of which is that they “will incorporate ESG factors into investment analysis and decision-making.” This investing approach, widely referred to as ESG integration, considers relevant and material ESG factors in investment analysis and decision-making using a consistent and systematic methodology. The consideration of ESG issues in investment analysis is intended to complement and not substitute for traditional fundamental analysis in active management that might otherwise ignore or overlook relevant factors. As for passive investing, ESG factors are typically considered in the construction of indices via negative/exclusionary screening, best in class and norms-based screening as well as weighting variations, either up or down. Setting aside the consequential questions of whose ESG scores are used in the analysis and their meaning, which are widely acknowledged to differ from firm-to-firm, ESG raw data and scores, now offered by some 600 firms by some accounts, are used by active managers to inform their views about buying, holding or selling a stock or bond issued by companies or other entities. This approach does not necessarily translate into an aggregate portfolio with higher ESG scores. For example, after due consideration of the relevant risks and opportunities, an active manager may decide to buy ExxonMobil (XOM) based on its growth and earnings potential over the intermediate-term or sell Tesla, Inc. (TSLA) due to poor governance and reputational risks. The portfolio’s aggregate ESG score fails to capture these considerations.

- Third, the Economist states that “American firms seem to be defining their own rules; some simply sign up to the PRI in the sole hope of attracting green-conscious investors with little to show for their claims.”

- Facts: Unlike Europe that has adopted a set of rules that, according to the Economist, are “tedious and sometimes misguided,” the SEC is still considering but has not promulgated guidelines for classifying sustainable funds. Also, the US funds industry has only made limited attempts to address the classification and definitional issues. In addition to contributing to confusion and misunderstanding, the absence of definitions and guidelines makes it much harder to conduct performance or greenwashing research. Further, the article implies a relationship between signing on to the PRI principles and green investing, yet none of the six PRI principles are linked directly to positive societal outcomes. This linkage, however, is consistent with the general tendency to conflate ESG integration with socially responsible investing, ethical investing or green investing.

- Fourth, according to the Economist, “…sometimes greenery is even used to keep assets under management growing even as managers post sub-par returns.”

- Facts: There is no reliable evidence yet to indicate that ESG integration produces higher or lower investment returns over the intermediate-to-long-term time horizons. In large part, the lack of reliable evidence has to do with the fact that ESG has a definition problem and a coherent understanding of what is meant by ESG integration is lacking among investing practitioners. Because of this, but also due to the large number of fund conversions or re-brandings to sustainable investing strategies and the limited track record associated with ESG integration, identifying cohorts of like funds over a sufficiently reasonable time interval to effectively evaluate performance results is challenged. At the same time, returns based on short time intervals can be skewed by shifting market dynamics to produce positive or negative performance differentials, as was the case in 2021-2022 when overweighting growth-oriented technology companies due to their generally higher ESG scoring and underweighting fossil fuel companies in ESG equity portfolios led to periods of outperformance by some funds pursuing a sustainable investing strategy or approach. Since the start of 2022, however, the performance advantage has narrowed or even reversed. Touting the potential for outperformance by some US based fund firms has proven to be a marketing misguided strategy. On the other hand, there is a somewhat stronger body of evidence in support of the view that socially responsible investing, because this form of investing has been around for many more years, produce below market-based rates of return. Even here, the conclusions may be attributable to the limited number of socially responsible funds, their varying approaches to socially responsible investing and the smaller size and less proficient investment management expertise exhibited by the management firms serving as advisers to these funds.